Premiere: 27 Oktober 2022. Weitere Vorstellungen: 28.-30. Oktober 2022 in den Sophiensælen, Berlin

— scroll down for english —

Vor 100 Jahren erblickte die Figur des Nosferatu im Schein der Berliner Filmprojektoren erstmals das Licht der Welt. Über die Jahrzehnte blieb die monströse Vampirfigur, geschaffen von Max Schreck in F. W. Murnaus Stummfilm Nosferatu: Symphonie des Grauens und neu belebt von Klaus Kinsky in Werner Herzogs Remake von 1979 ikonografisch unsterblich. Und unheimlich ähnelt die gesellschaftliche Situation, in der wir uns heute befinden, derjenigen der Stummfilmpremiere um 1922, als die Spanische Grippe gerade überstanden war, als Inflation und Wirtschaftskrisen die Welt ebenso beschäftigten wie politische Unruhen und das Erstarken von Nationalismen, als die Unabwendbarkeit einer bevorstehenden Zeitenwende einherging mit der Identifikation von “Anderen” und der Suche nach Sündenböcken. Ist es nicht auch heute wieder Zeit für einen Vampir?

Der Begriff des Queering geht dabei über ein enges Verständnis in Bezug auf soziales Geschlecht und Sexualität hinaus, denn Vampire sind in diesem Sinne ohnehin immer schon queere Wesen: als Pan-Sanguivore gieren sie gleichermassen nach dem Blut aller Gender und sie leben außerhalb der Beschränkungen heteronormativer Zeitlichkeit. Natt jedoch meidet in ihrer Lesart solch anthropomorphisierende Perspektiven – ihr Nosferatu ist weit entfernt davon menschlich zu sein! Die Performance bewahrt ihn vor dem bei Monstern sonst üblichen Entwicklungsweg: werden sie zunächst gefürchtet und geächtet, so sollen wir im nächsten Schritt mit ihnen sympathisieren, bis wir sie schließlich ganz vermenschlichen. Diesen letzten Schritt geht Natt nicht und stellt einen Vampir vor, der sich unumwunden seiner Monstrosität erfreut.

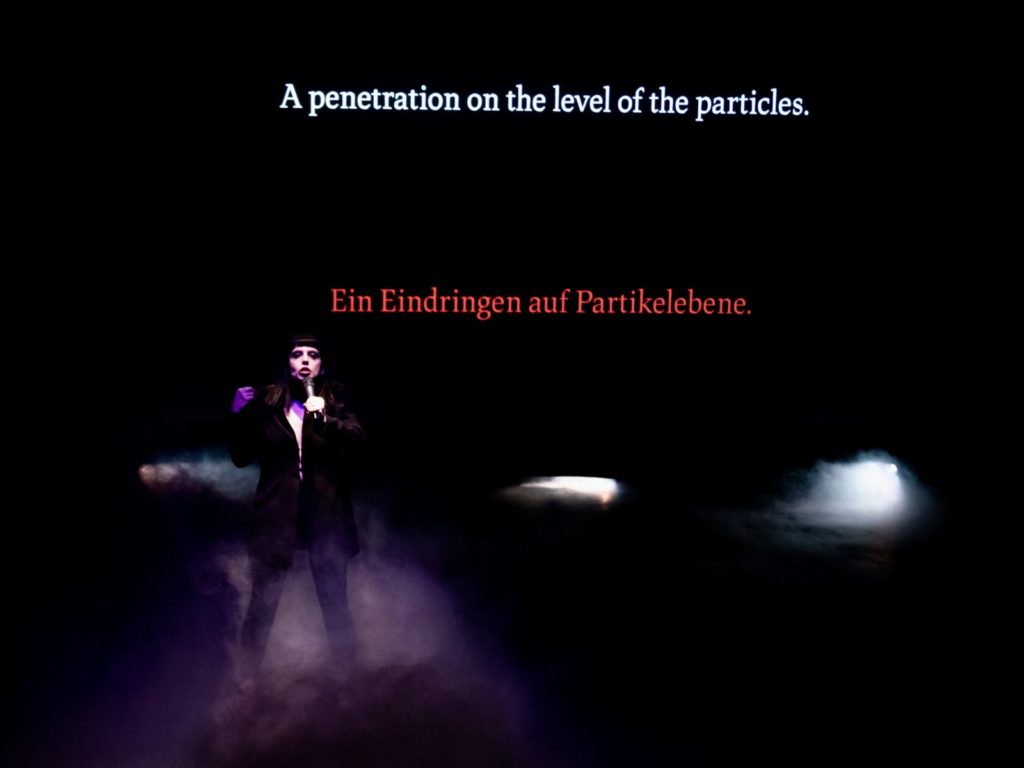

Das Kontemplative von Queering Nosferatu liegt nicht nur im künstlerischen Zugang von Anna Natt, sondern auch in der atmosphärischen Präsentation. So steht die Performance in organischem Zusammenhang mit der räumlichen Klangskulptur, die der Experimentalmusiker Robert Curgenven mit einer auf der Bühne live-gespielten Pfeifenorgel und geklonten Orgelklängen mit einer 6-Kanal-Klanginstallation im Raum gestaltet. Curgenven arbeitet ganz bewusst mit der physischen Erfahrbarkeit des Klangs, der Raum und Körper zu durchdringen und in Schwingungen zu versetzen vermag

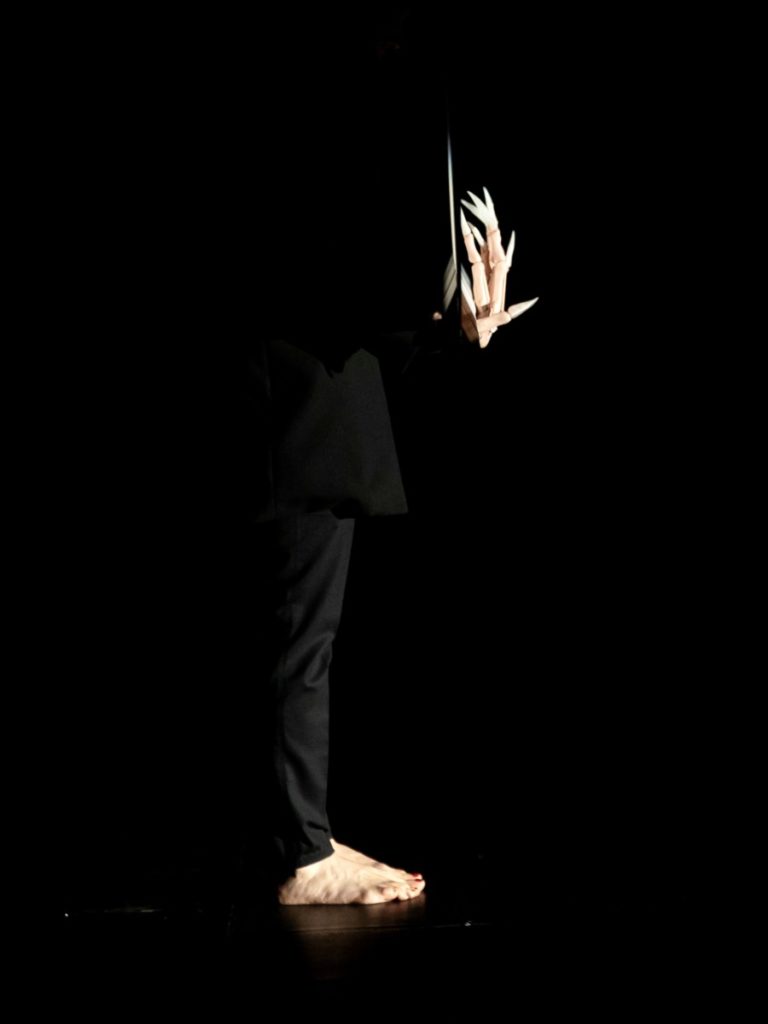

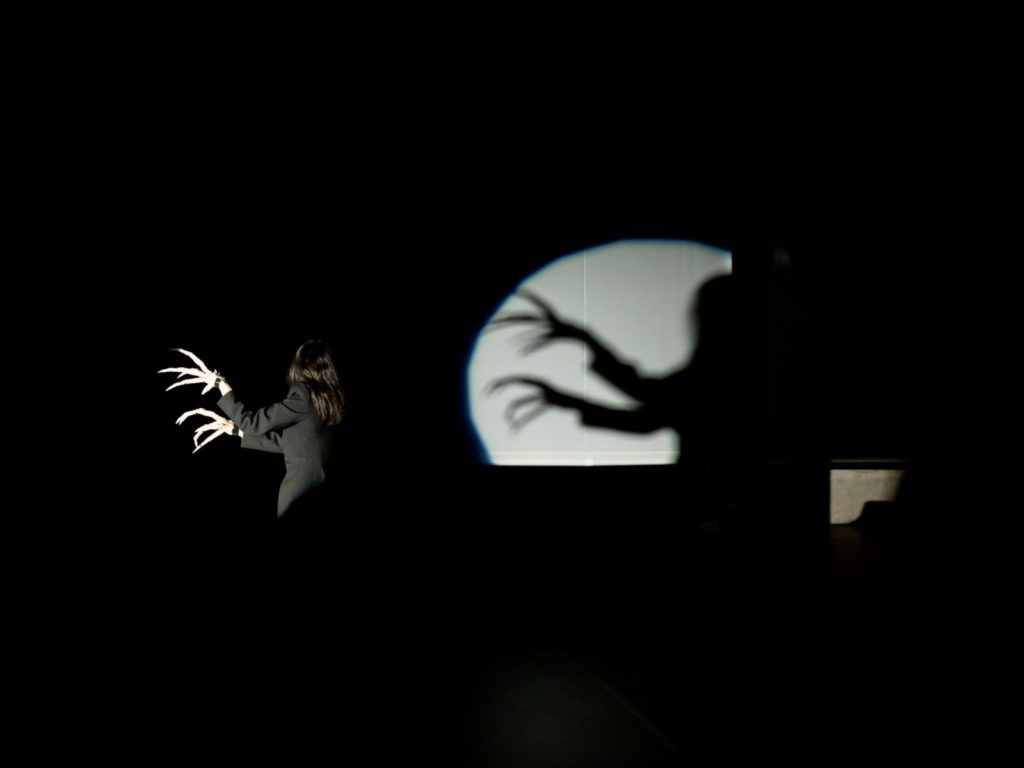

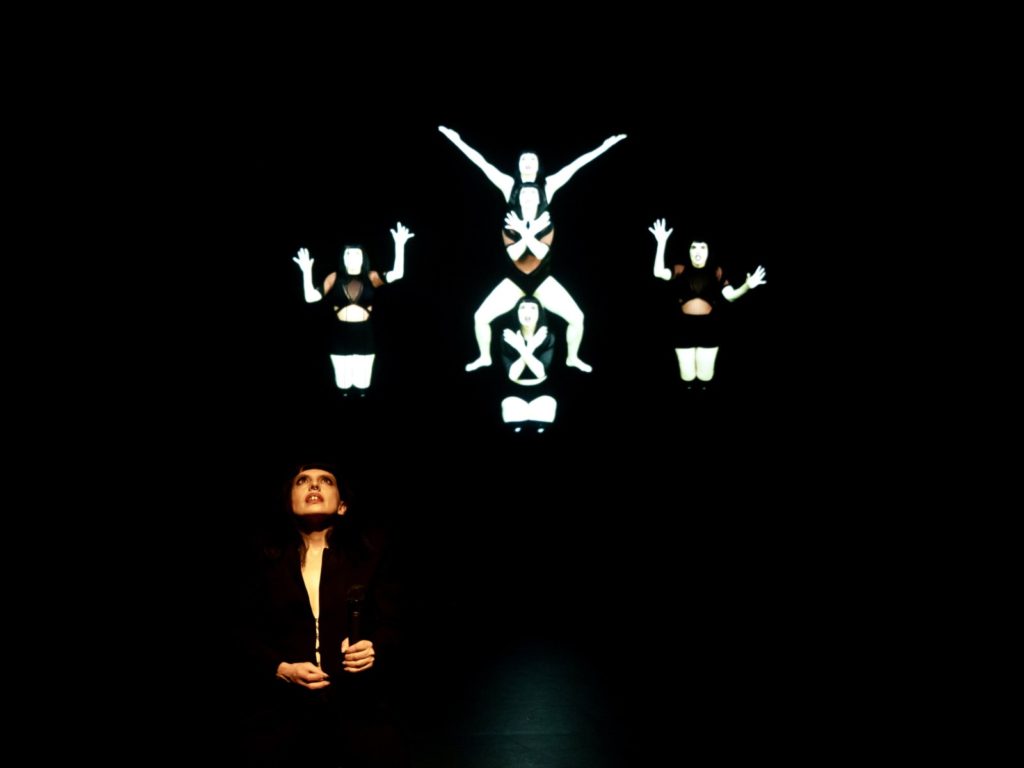

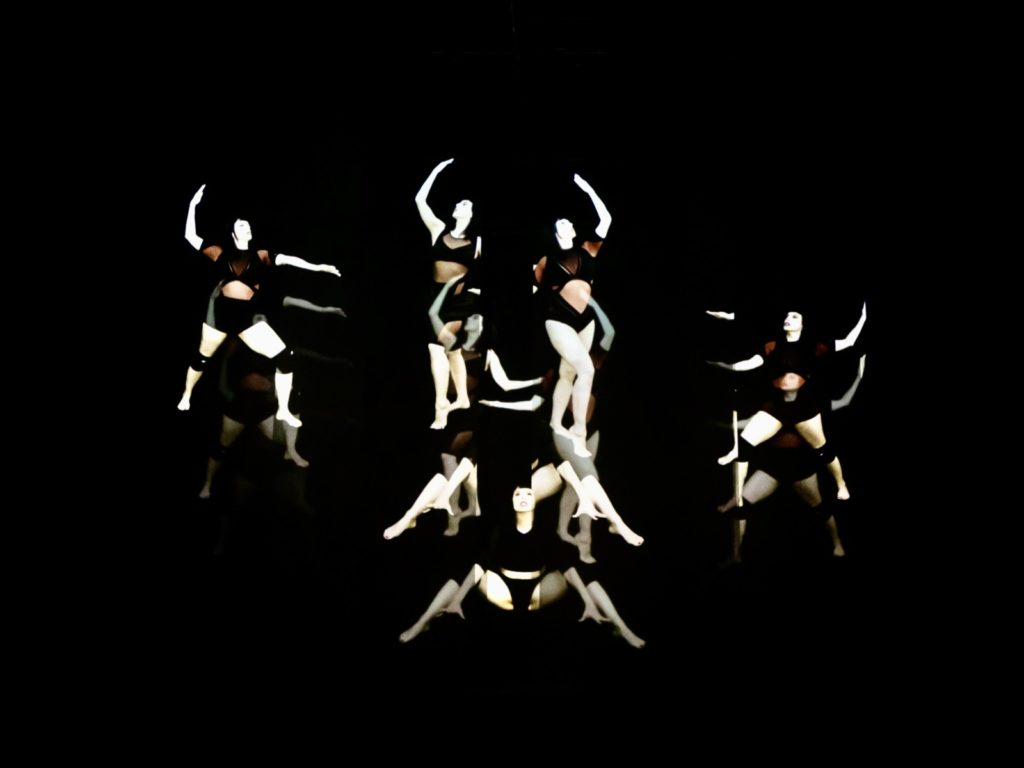

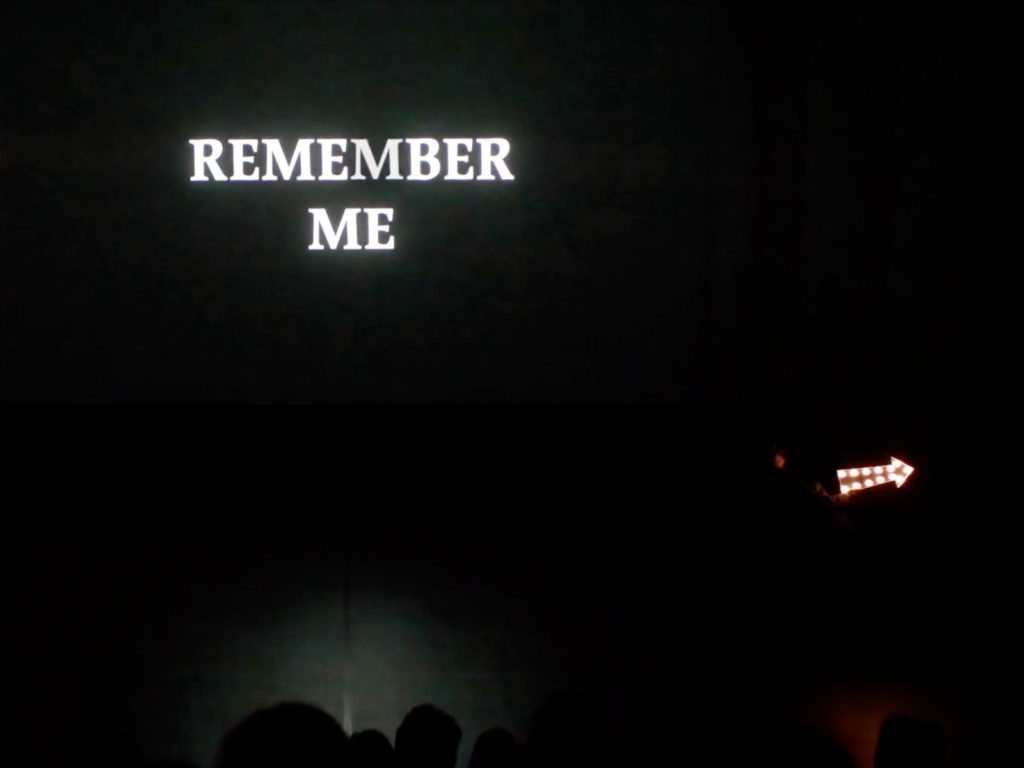

Zentral für Queering Nosferatu ist ausserdem die experimentelle Videoperformance und Multi-Screen-Installation von Anna Natt und Dalia Castel, eine Hommage an jüdische expressionistische Choreografinnen, die das Groteske der expressionistischen Gesten hervorhebt und die Performance in Beziehung zur ursprünglichen filmisch-expressionistischen Darstellung des Nosferatu von 1922 setzt. So beseelt der Vampir sowohl die Bühne als Untoter als auch die Leinwand als ewige Kreatur – und fordert sein Gedenken ein, indem sein Bild sich uns ins Gedächtnis brennt.

Konzeption, Künstlerische Leitung, Choreography & Performance: ANNA NATT

Ko-Konzeption, Künstlerische Mitarbeit & Produktion: MATTHIAS PÜSCHNER

Komposition, Sound Design & Orgel: ROBERT CURGENVEN

Video & Videoinstallation: DALIA CASTEL

Choreographisches Outside Eye: YALDA YOUNES

Dramaturgie: MAYA WEINBERG

Lichtdesign: LÖIC ITEN

>> WEITERE INFOS & TICKETS VIA SOPHIENSÆLE

>> FOLGE NOSFERATU AUF INSTAGRAM

A production by Anna Natt in cooperation with SOPHIENSAELE

Hauptstadtkulturfonds

Theaterhaus Berlin Mitte

————————

— ENGLISH —

————————

QUEERING NOSFERATU

A Performance by Anna Natt

Premiere: 27 October 2022 – Further Performances: 28 – 30 October 2022 at Sophiensæle, Berlin

One hundred years ago, the figure of Nosferatu first saw the light of day in the glow of Berlin’s film projectors. For decades, the monstrous vampire first played by Max Schreck in F. W. Murnau’s silent film Nosferatu: Symphonie des Grauens and reincarnated by Klaus Kinsky in Werner Herzog’s 1979 remake, has been an immortal icon. And there is an uncanny resemblance between the social situation we find ourselves in today and that of 1922, when the film premiered. The Spanish influenza pandemic had just passed, the world was worried about inflation and economic crises as well as political unrest and growing nationalism, and the inevitability of an imminent change of epoch was accompanied by the identification of “others” and the search for scapegoats.

Is it not time for a vampire again today?

In the contemplative performance Queering Nosferatu, Anna Natt uses Nosferatu’s centenary as the occasion to develop a queer reading of this particular vampire character through a highly personal engagement with some key moments from Murnau and Herzog’s films. Natt thoroughly identifies with the vampire. The monstrous, insatiable, and excessive nature of the vampire corresponds with that of the feminine, which heteronormative discourse defines as the “other” and as a threat. In Natt’s performance, it is allowed to be, it is an integral aesthetic-productive element. The grotesque nature of Nosferatu’s movements and gestures is embraced, as it offers a different way to confront one’s own aging, with more stiffness and loss of technique than is permitted in the world of dance and performance.

Here, the concept of queering goes beyond a narrower understanding of sexuality and gender identity, for vampires are, in that sense, certainly queer beings: as pan-sanguivores, they hunger equally for the blood of all genders and they live outside the confines of heteronormative temporality. Natt, however, circumvents this kind of anthropomorphizing perspective in her reading – her Nosferatu is far from human! In the performance, the vampire is spared the trajectory usually assigned monsters: first they are othered and feared, then we are made to sympathize with them, and finally they are humanized. Natt rejects this last step to present a vampire who unapologetically finds pleasure in his monstrosity.

The contemplative aspect of Queering Nosferatu lies not only in Anna Natt’s artistic approach, but also in the atmospheric presentation. The performance is organically connected to the spatial sound sculpture created by experimental musician Robert Curgenven with a pipe organ played live on stage and cloned organ sounds using a 6-channel sound installation in the space. Curgenven intentionally works with the physical experience of sound, which is able to permeate space and body and set them vibrating.

Central to Queering Nosferatu is also the experimental video performance and multi-screen installation by Anna Natt and Dalia Castel, an homage to Jewish expressionist choreographers that accentuates the grotesqueness of expressionist gestures and relates the performance to the original cinematic expressionist representation of Nosferatu from 1922. Thus, the vampire inhabits both the stage and the screen – moving as undead body onstage and as eternal creature on the screen – and claims his memory by burning his image into your mind.